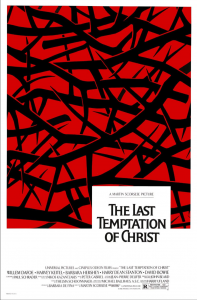

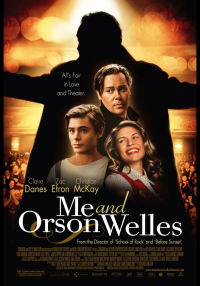

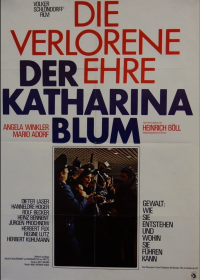

This week on Film at 11, Jeff Godsil takes on Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ, adapted from the Nikos Kazantzakis novel, while matthew of KBOO's Gremlin Time looks at Richard Linklater's Me and Orson Welles In our book corner we reflect on the new BFI monograph on The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum. from 1975, directed by Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta from a tale by Heinrich Böll.

________________________________________________________________

The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum or Die Verlorene Ehre der Katharina Blum oder: Wie Gewalt entstehen und wohin sie führen kann, was released in 1975 and was remarkably timely, given the lag time between public events and private showings. It was written and directed by Volker Schlöndorff and Margarethe von Trotta,, based on the novel by Heinrich Boll, which was itself originally serialized in Der Spiegel, as a critique of the chain of newspapers in the Springer empire, and their attack on leftists and unscrupulous way of exposing the private lives of citizens. It's timeliness continues to this day.

Now there is a brand new British film Institute Film Classics monograph on the film, that explicates now what is mysterious about the work a quarter of a century later. drama. Writer Julian Preece is Professor of German at Swansea University, UK and has written books on Günter Grass, and the Baader-Meinhof and the Novel. He covers all the background information you need, both about the book’s writing, the film’s production, the political background, the cinematography, set design, and music, and casting choices that would be obvious to contemporaneous German viewers, but not so much today.

The premise is something along the lines of "they made her a criminal," as if having emerged from the social problem films of Warner Bros. in the 1930s. Katharina Blum (played by Angela Winkler) is a young woman who has withdrawn from the society of men except for those by whom she was employed, as housekeeper and helpmate. In Cologne there is a five day festival called Carnival, and the movie takes place during those five days. On the first day she goes to a party at her aunt’s house, and there meets a man who gives his name as Ludwig (Jürgen Prochnow), and her guard is dropped, and they spend the night together in her apartment in a brutalist style public housing building that the film enjoys decrying visually. What we know and she doesn't is that Ludwig has been under police scrutiny as a possible terrorist. When the police raid her apartment the next morning he is not there, and she is taken in for questioning as an accessory. Much of the film is taken up with the various interrogations she undergoes, and at times they can be exhaustively specific. For example, the investigators add up the mileage on her Volkswagen and determine that there are about 500 km unaccounted for. Where did she go? Katharina says at night when she had nothing to do she likes to drive around the country rather than sit home and drink in front of the television as do so many women she knows. We are reminded again and again how the privacy of this person is invaded on the vague suspicion that she is part of a terrorist cell. Meanwhile, a journalist who works for an entity known only as The Newspaper colludes with the police on the one hand and makes up quotes and stories for his newspaper on the other. What happens at the end of the five days results in a film that, for example, Billy Wilder, called “simply the best German picture since Fritz Lang’s M."

To two quotes from the book clarify the film’s effects and techniques. The final paragraph of the book is a great summary of what it is about:

“Inspired by one of the first German crimes stories published on the eve of the French Revolution about injustice in a class-based legal system, Katharina Blum has migrated across the media (fiction, drama and film) in remakes and adaptations since first (re-)imagined in 1974 by Heinrich Böll and translated to the screen for release the following year by Margarethe von Trotta and Volker Schlöndorff, who worked closely with the author. The film was received in the book’s wake and reinforced its impact. The directorial duo, specialists in literary adaptations, turned a political pamphlet in the form of an ironic short novel into an eerie, suspenseful thriller. The film benefits from an amalgam of international styles, American, French, Greek, and a mix of high modernism, documentary and popular forms in its reconfiguring of a tale of group victimisation of an individual. In contrast to so many twentieth-century German narratives of fascistic behaviour, the individual fights back, which is what has made Katharina Blum emblematic in contemporary Germany and beyond.”

Along with the innovative cinematography by Jost Vacano, which the author suggests took some inspiration from the sanitized anomie of paintings by American George Tooker, the musical score by Hans Werner Henze is not what you would expect from a thriller in the genre of for example Z, edgy, unnerving and dissonant. From the book:.

Henze’s influence on the film’s narrative structure appears to have been considerable. His concert suite has three themes: Katharina’s lament; violence emanating from the state and press; and hope represented by Götten (Ludwig) and the prospect of being reunited with him. Their unexpected meeting marks the point in the music when their two themes coincide, though it is striking that this scene in the film is not scored. The music signals that even though Blum must go to prison for murder, she has overcome her despair. Henze’s dissonant extradiegetic score contrasts with the music heard in the film, first at the Café Polkt and the carnival party, and finally with the church choir at Tötges’ funeral. It accompanies only certain characters (Blum herself, Götten and Beizmenne, but not Sträubleder, the Blornas or any of Blum’s other friends), objects (telephones, the Zeitung, Blum’s car), locations (the apartment block and the police station) or sequences (the black-and-white surveillance of Götten). Tötges’ appearances are unscored, presumably because he does not intrude directly into Blum’s life until their fatal meeting, when his arrival at her door is greeted with the first crescendo of noise, the second occurring right at the end of the film as the false disclaimer appears on the screen. Following Blum’s second car journey, when she travels to see Götten, only to discover that he has already been apprehended, intra- and extradiegetic sound briefly merge as Henze’s composition gives way to a police siren. As well as signalling the uncanny qualities of events or objects which are not in themselves usually threatening, Henze scores Blum’s inner journey, with all its discordances and anxieties, and suggests the nightmare contained within the everyday. Henze himself had been the object of press campaigns after the premiere of his oratorio The Raft of the Medusa, which he dedicated to Che Guevara, was cancelled in November 1968 on account of disturbances by protesters, whom Henze said he supported. Like Böll, he wanted to express the fruits of his experience in an appropriate format and contribute to a fightback.

Songs and music are integral to carnival. There are snatches from three carnival pop songs (in German Schlager), each of which includes a foreign location where carnival is celebrated – Mexico, Barcelona and Rio de Janeiro. ‘Carnival in Rio’ is sung to the tune of ‘Cielito Lindo’ beloved of Mexican mariachi bands, sometimes known as the ‘Ay, ay, ay song’ because of its refrain. The musical references are missing in the novel, but they match the exotic sources for the costumes.“

Professor Preece tracks Katharina Blum’s stoicism, and her "finding her voice" in the face of nonstop condescension from her interrogators, as in so many people around her use the German “chen” suffix, a diminutive, as a friend who speaks German pointed out (though the diminutive was not translated in the subtitles of the version we saw).

Katharina Blum was remade as a TV movie, and in fact there are numerous film adaptations and theatrical versions of the movie, but the closest thing in subject matter is the 1981 Paul Newman – Sally Field's film Absence of Malice, where Newman is the innocent citizen whose life and friends are splashed across the pages unfairly, but in typical Hollywood Cinema fashion, he turns the tables on his oppressors. Except for certain longuers, such as a funeral sequence, this film is relatively fast paced and ruthlessly realistic, and deserves to be revived for contemporary viewers.

- KBOO