Let's Talk! Creating Beyond Limits: Anna's Dyslexia Story

Web Article written By Andrew Kobus and Hannah “Asher” Sham

July 17, 2024

What do you see when you look at a painting? Well, for some with dyslexia, they see things that not all of us can, and can pick apart the minute detailing within moments of glancing at an artistic piece. Anna is a PCC student majoring in sonic arts and music. She’s also a singer-songwriter and has dyslexia. But, the road to becoming such an accomplished artist has been far from easy. In this podcast, we will look into how dyslexia is different from autism, and Anna’s triumph over the status quo on what’s “normal” for people with dyslexia.

"The Dream That Came True" by Anna

Dyslexia vs. Autism: What Makes Them Different?

It is important to preface that dyslexia and autism symptoms differ widely from person to person. No two people have the exact same type of autism or dyslexia. As Amanda Antell said, “Autism is not the same between any person. Anyone.”. According to an article by Cross River Therapy; Dyslexia and autism are both neurodevelopmental conditions that last throughout a person’s lifetime. Shared symptoms include trouble with communication, though the specificity of these symptoms may differ. Some common symptoms of autism may include sensory issues or emotional development issues. On the other hand, some common symptoms of dyslexia may include disorganized writing or speech, and trouble focusing. People with autism or dyslexia may have different ways of perceiving the world, and different learning strategies than neurotypical people.

“If I'm reading a book, I will think of the picture, but I will never think about the words. I will never understand the concepts the same way as other people, because my brain doesn't see that.” - Anna

Dyslexia can allow the person to visualize big picture concepts, making the simultaneous experience of learning and communicating both easier and more difficult. However, while (some) dyslexic people may fall into the category of visual learners and thinkers, some people with autism do not fall into that category at all.

“...I'm kind of the opposite of you, where I can't really picture things in my head at all. All I see are like the words and I know how to describe things.” - Amanda Antell

Local Art & Music Groups and Clubs

If you are a fellow art lover, like Anna, and want to express yourself through the arts; here’s a compiled list of local Art & Music groups, clubs, classes, and activities you can join:

Community Resources

We also understand that having resources and / or a community to come alongside you on your journey is sometimes what we need. Whether you’re a student or looking to be a part of a community, here’s a list of resources in PCC:

Portland Community College programming for students with disabilities is called the DCA, or disability cultural alliance. Accessible Education and Disability Resources (AEDR) runs the DCA, and is also in charge of accommodations for students and staff, creating formatted content for curriculum, and training staff and faculty on disability awareness. AEDR also contributes to many panels and committees to help shape PCC's future toward accessible design known as Universal Design. AEDR has offices on all campuses, and at SE campus there is a room known as The Hub that is used for events and training sessions. The Queer Resource Center is also a place to go to if you are a student in need of a community who embraces those that are just a little different.

Resources:

Episode Transcripts

Ai-generated transcripts edited by Miri Newman, Andrew Kobus, and Hannah "Asher" Sham for grammar, punctuation, and syntax errors.

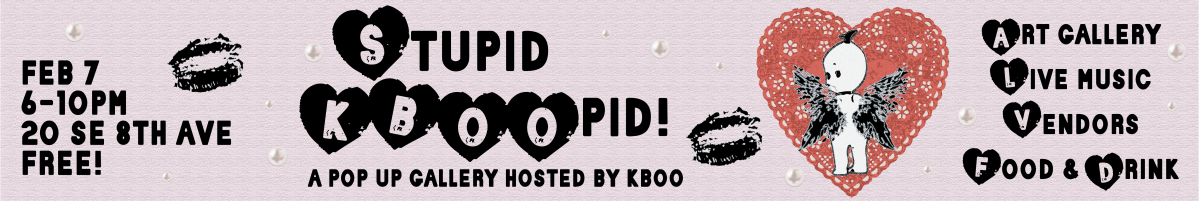

Naia: You're listening to Let's Talk! Let's Talk! Is a digital space for students at PCC experiencing disabilities to share their perspectives, ideas, and worldviews in an inclusive and accessible environment. The views and opinions expressed in this program are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or positions of Portland Community College, PCC Foundation, or KBOO FM. We broadcast biweekly on our home website, pcc.edu/DCA, on Spotify, and monthly on KBOO community radio 90.7 FM.

Amanda Antell: Hello and welcome to today's episode of Let's Talk Autism. I'm your host and producer, Amanda, and I'm excited to present my new guest, Anna. Anna is an amazingly talented woman with dyslexia, with her condition contributing to her beautiful work. Throughout Anna's story, she described the trials and tribulations of having dyslexia in her school district system. In particular, she described the intense persecution that caused years of trauma and emotional shutdown. However, Anna came out the other side stronger, knowing her purpose and owning who she is. I hope you enjoy listening to Anna's story as much as I have.

Interview Starts: Introducing Amanda and Anna

Amanda Antell: Thank you, Anna, for joining me today on Let's Talk Autism. I'm really looking forward to having you as a guest. As we've talked previously before this interview, you're an amazing person, you're an amazing artist, and I think the audience is just going to love hearing what you have to say in your story.

Anna: Thank you so much for having me here. It's wonderful to be here.

Amanda Antell: I hope that you have a great time talking with me today, so let's go ahead and start with introductions. So, my name is Amanda, she/her pronouns. I am finishing up an animal science degree at Oregon State. I'm applying to vet school this year, and I was diagnosed with autism at age 31.

Anna: Hi, my name is Anna, she/her pronouns and I'm going right now to PCC. I am a sonic arts and music major. I'm going to be graduating this term and I am an artist. I am a singer-songwriter, but I also do 2D art. I paint mainly on canvases and I use also mixed medium. I have dyslexia. I have a problem with math.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, I've always had trouble with math too. I don't know if it's the same thing you have, but to be honest with you. I have to do what's called the lather-rinse-repeat- method when learning math- where I have to basically repeat the same kind of math problem over and over again for my brain to understand it, but I also can't like start in the middle of an equation if like different parts of it are given in a story problem, you know?

Anna: Yeah for me being both dyslexic and having dyscalculia, it means that I have a problem reading the story problem, but also understanding it and putting it into context. So when they give it to me, I'm pretty much doomed, because when I read it, I won't understand it the first time around anyhow, because there's certain words I probably don't know, and I'm going to miss certain things and then the second time around, I'm still not going to understand it. The process of me seeing certain words, and the understanding of it, doesn't go in context, I can't take out like, "Oh, You're saying 'and', what does that mean?" or "a sum" or something. It's really hard for me. Because what happens to my brain is when I read, I can see the words in my head. And so that's why I'm like guessing which word comes next and what the words sound like. Because my brain just automatically does it. And then somehow I'm going to stumble and I won't know a word. So that happens. And then if you have the math point of it, where my brain, when I see numbers, I can understand "two times two", but when I calculate that in my head, I can't put two and two together and say, "two times two"; sometimes I have to use my hands, like count with the fingers, or I have to use a calculator. And that's really the most I can do because my brain itself just turns off. Like it doesn't see anything. Which is really weird because as an artist my brain is always working. It's always seeing and taking things in. But when it comes to like math or anything with reading, it's just dead. It's dead when it comes to those things. If I'm reading a book, I will think of the picture, but it will never think about the words. It will never understand the concepts the same way as other people, because my brain doesn't see that. This week we were having a conversation in one of my classes and nobody knew what this word meant. It's so bothersome when I don't know a word because my brain just goes black and it's almost like anxiety. Because it's like, "Oh no, I don't know this word and it feels so empty. What is this word? What is happening?" But it can't comprehend it. And then I have to look it up and then it's like, "oh, okay, this is what it means!" And I was the one person who was dyslexic in the room, that had to look it up because nobody else wanted to look it up and explain it. Because I'm like, "well, I need to… know" because my brain is not gonna stop having this weird feeling and sensation of emptiness until I know what it means and look it up. So, that's what I did.

Different Minds, Different Pictures

Amanda Antell: I think that's really interesting. It basically sounds like you're all visual- correct me if I'm wrong-, where I'm kind of the opposite of you; where I can't really picture things in my head at all. All I see are like the words and I know how to describe things. Like those exercises where it's like: picture you're on an oceanside or in a field of flowers or something? I can pretend, like I can close my eyes and literally describe a field of flowers, or an ocean side, because I know what both of those look like, but I'm not seeing anything in my head. I'm just going along with it.

Anna: And that's a lot of people, actually. A lot of people don't see the picture that much, they see certain things in there, but they can't imagine it. Something really good with people with dyslexia and people who cannot read words, but they see pictures; they can actually imagine and capture it. And they might even put things in there in context and see meanings that other people can't, which is very interesting. A lot of people with dyslexia are either very scientific, they are so detailed in science and math, or they're really detailed in art and music So it's like there's two different sides. But a lot of us are very detail oriented. We're really into that. And we can see bigger pictures when other people don't. And we hate it when we're talking to somebody and we're like, "You don't get it! You don't get it!" Because our own mind sees a big picture and then sees all the little things, and we can feel it out because we haven't been able to read the text the same way as others, but we can feel what these mean and the deeper meaning. It's very interesting, you don't read the lines, but you read in between the lines.

Amanda Antell: I think that's really cool. Cause like I said, I can't picture anything. I really cannot picture things in my head at all. My teacher really wanted me to become more of a visual thinker, cause with chem it actually is a lot of art, believe it or not, it's like drawing a lot of chemical structures. I feel like you'd be really good at that, and I of course suck at that, and this program called "Chem Draw" saved my life with lab reports. I can tell you how things are working and why the molecules form the way they do, but I could not draw them to save my own life.

Anna: It's so funny, because it's really interesting when we think about it. That's why they started making these wooden molecules building-sets–because a lot of people have that problem. And, for me, I can just see it in my brain. Like, "Oh, this would go here, here, here." "oh, branches out here. And I see the pattern." But other people understand how that works, but they don't understand how it builds out into this daisy chain or they don't understand the bigger picture. Like the similarities and always connecting in a picture form. They just see it as numbers and scientifically this is how this works and this is how this works.

Amanda Antell: Yeah, and one thing I think you, correct me if I'm wrong, but if you were given a polysaccharide chain, you probably would be able to predict exactly how it would go because as long as you know the first basic part of the pattern, which is basically one to three bonds anyways, you could probably just predict the entire sequence, correct?

Anna: Yeah. And actually that was the one weird thing when my teacher was talking in chemistry and was like, "Oh, this is how this goes." And she gave us the start of the equation. And it was like, just the molecules connecting. And then I could tell 20 molecules down, how it would connect into this sheet of molecules going together. And it was weird. It would be in my brain, this whole sheet. And the really funny part is that actually hinders it because I'm seeing more than what they want me to see and then they're like, "you're thinking too big!"

Hey, Teacher, Leave my Brain Alone: Disagreements with Teachers

Amanda Antell: I don't think it's that you're thinking too big. I think it's more like you see the complete picture that the teachers can't. They're just basically regurgitating what they were taught. So I don't think you're in the wrong there at all.

Anna: You're right. And everyone that knows me, they're like, "You're so good at this, why do you struggle so much?" I'm like, because I see a bigger picture, I can see it in my mind. But when I put it onto paper, for a test and it's all reading. It doesn't comprehend the same way. And then, teachers always go, "You should just ask more questions." And I'm like, "I am dyslexic and I don't even know what I'm struggling with because my brain doesn't want to tell me, "Oh, you're struggling in this." 'cause more or less, I understand it. But I cannot put it on paper.

Amanda Antell: Well, I think that's also stupid. Because I think a lot of students really have trouble verbalizing what they exactly have trouble with anyways because they're like trained to feel shame, especially in STEM classes where it's like only the best of the best make it in these classes. So it's like, "I can't ask questions. I can't show weakness."

Anna: Yeah. And then it gets really hard because it's like, "Oh, we all have weaknesses, but we just can't show it." and it's like we become frozen. "We can't have this weakness!" But, the truth is we all have weaknesses. So then we become like a mushroom or something frozen in a black box or a black hole. And we don't have any emotions now. We can't express ourselves. We're pushing ourselves to the breaking point to be something we are not; to a point where you're just unable to really comprehend anything else because you're using all your energy to not show weakness, when that's not how people work. And I've been through that myself. Because there's been a lot of people in my life, like "you're disabled. You can't show weakness!" I had a teacher tell me when I was in sixth grade "You cannot cry! Don't cry! Stop crying! Don't show that emotion!" So for the longest time, I wouldn't cry. To this day it is very rare if you see me cry ever because I can't feel that emotion the same way as others. I can't reciprocate it because I was told and abused "You're not supposed to cry. You're not supposed to do this. You think that's your scapegoat, of a thing, crying or whatever." And I'm like "No, that's not how it works." I'm 24 and I'm finally getting my associate's degree. It took me a while because from being persecuted since I was probably around five and my mom and dad both knew I was disabled really young. So, they didn't put me in preschool. So, I only got into kindergarten through 12th grade and then college. A lot of the people, just when I got into kindergarten, they started hurting me. In the old days, those Scholastic books, you had to build the little booklet and then you would have to put staples in it. And I was trying to do this and it was on panda bears. I remember very fondly because the incident will forever be in my brain. This is me in kindergarten and I was stapling it, not left to right, but right to left because that was how my brain thought of it. Well, they didn't like that. So, my teacher literally goes to me and is like, "This is not what we do!" And I'm like, "But in Asia, they do that." "Are you Asian?" And I'm like, "whatever." So, I've been always persecuted; coming from that mentality, when I got out of high school, I was like, "I need some time to find myself and find my emotions." Because, I had almost nothing. And that was really when art and other things really came to play because I started being like, "Okay, I need to get back into art." But, then I didn't know how to get back. What was I supposed to paint? When I'm drawing weird doodles all the time, when I was a kid, what were they meaning? You know, that was one of those things. And then I found out, "Oh, it was because I actually had these emotions and I had these things that I could do." I just never realized and put them into place. It's kind of like all these things are happening in my life and I never really put the puzzle pieces together. I never really put them together until I got older. Like I got to become an adult and I realized, "Oh, all of these things go together."

Amanda Antell: First of all, don't be ashamed of getting your associate's degree at 24. I'm 34 now, as much as I hate admitting my age and I'm going to get a postbac degree in animal science. And I, the reason I didn't get an undergrad degree in animal science when I was in my twenties, like you, was because I didn't have my autism diagnosed and I could not get the support I needed at university. And I'm responsible for my own actions. I'm not trying to blame the university for my poor academic performance. But, because I couldn't get the academic support I needed; I was forced to get a degree I really didn't want. And the degree itself is like a scar for me. I didn't even want the degree, but my mom really wanted me to accept it. So I did. But to me, I hate even looking at it. I'd prefer just burning it. Whereas this post bacc degree is a completely different feeling because this is a degree I actually wanted in animal science and I can use this to pursue veterinary medicine, which has always been my passion. So we have different stories, but in terms of the persecution aspect, because I was undiagnosed for the longest time I was isolated sometimes in class where I basically was too slow in math, but too advanced in writing. So, teachers really didn't know what to do with me, and in kindergarten in particular, I had a teacher similar to what you just described; where she was this militant teacher who never should have been in charge of kids, and she would get angry at me if I was slouching in the story time circle.

Anna: Oh gosh.

Amanda Antell: We all had to be sitting up straight, or I would lay down or something, because you know I'm autistic and if I'm bored or if I'm not interested in something, of course, I squirm and wriggle or whatever. And, she would just get angry at the smallest things and apparently I wasn't holding scissors correctly. Then it's like she got on my case, sometimes, about not coloring inside the lines, like I was never an artist like you. But, my response rather than trying to color inside the lines more was looking at her and going straight outside the line.

Anna: Just to make her more mad and annoyed.

Amanda Antell: I just didn't care as a kid. If I didn't like an adult, that was it. I just wasn't going to listen to them.

Anna: I get you. because, my partner is the same way. Yeah, he's like, "don't look back at my past!" "When I was a kid, I was a rebellious kid!" And he would be like, to this day. "You don't look like that." But, when people around you, take you and say, "we want you to be this way." There's two ways; you can accept it and try to become "into the box" or you can branch out and say, "Hey, I'm not going to accept what you're telling me and I'm gonna even be more rambunctious or make you more annoyed." Because the truth is a lot of times what these people are really angry about is just that you're different. And you're not in this mold. We're not supposed to be in the mold though! We're different. Everyone is different. Everyone has a different background story. Everyone has a different personality. Everyone is from a different country. Your DNA is very similar to other organisms, but you also have 0. 0001 percent DNA that is wholly yours and it doesn't have to be like the next person's. It's kind of crazy because people get this idea that you have to be like this and that's not how life works. And, for me, even with my disability, the school districts and everyone, they were like, "oh, dyslexia, you just grow out of it!", "we don't know how to handle you.", "We don't know what to do with you, And they just didn't want to do anything. Cause the people in the United States, and in most countries, they look at dyslexia as something that is "just a learning disability that you grow out of", or "you not working hard enough", or whatever. And they just put you in a room, isolate you, and say, "you're stupid and we don't want you around." And that was my whole life. To this day, it's kind of funny people who are disabled also are like, "Hey, I get funding from the government but, you're disabled and you don't get any of this?". And they can't fathom it, and I'm like, "well dyslexia Is looked at by the government, and everyone, as something that they don't want to support." There's probably so many people that are dyslexic that don't even know they're dyslexic because they will never get the actual diagnosis and they will never get the support they need. And, so they don't really get you and they don't want to have you around and they don't give you any materials to help you, so you have to learn everything by yourself. I survived, because I said, "I didn't want to be like the world." I knew I had different things that I could do. I know I have a goal and I want to get through that and I want to be something that they don't want me to be like they told my mother And my father; they were like, "they got a faculty person to make me proctor this test", and this test was literally for kids that were babies. At that time I was in sixth grade. So, think of it, a baby's test for a sixth grader is not going to be the same. So, they think you're just a baby still, and they just want you to think that way. Well, find out, "oh, she has too many words, or whatever, and we don't want her to be registered as disabled". So, they tried to throw away all my documents, that I was disabled. Luckily, my mom picked all of them up and walked out of the room. And when my parents walked out of the room, they're like, "yeah, she's never going to pass high school.", "We're never going to allow her to graduate.", "She's never going to go to college."; they really were saying that behind my parents back. Behind my own back. And from that day on, I was like, "I am going to be different than what they want me to be, I am going to pursue, I'm going to conquer, and I'm going to work hard." And that was what I did. And it was a lot of hurt that I had to go through to get there because I became what is called a scapegoat for all the teachers and everyone, because I was different. I was more quiet. I was more afraid that they were going to hit me or hurt me or do something or whatever. Because, the school system said, "because you're dyslexic, you shouldn't be able to do any of these things." They always were trying to make me something I wasn't. So, I was trying my hardest to fit in just by being quiet and just by being more distant than most kids. And, yeah, it kind of backfired.

Being Diagnosed by the Public School System

Amanda Antell: Your story really is incredible, and thank you for just sharing all of that. Just so you know; whoever the heck that was that told you, and your parents, all that stuff, to heck with them. They were wrong, very clearly. You're awesome. Your art is beautiful. And quite frankly, you'll be successful with whatever you do. And to be honest I wouldn't say I have a similar story to you, but there were elements of it that were fairly similar; where I was evaluated in elementary school by this guy that was hired by the school. I don't know who this guy was or what his credentials were, but looking back on it, he was probably like a quack. Anyways apparently he did some kind of cognitive test with me and he told my mother I would never learn to read. And this was before kindergarten, or something, so I had to have been like four or five or something like that. My mom never trusted the school district with any of my medical records again, but she did try to get me diagnosed. Because she did know I was very different; I think that's why I was evaluated. Autism just wasn't a thing in girls and people raised girls at the time. Like, it just basically was so unheard of, or just basically thought it just didn't happen in girls at the time, or in people raised as girls. So, despite taking me to several different experts, they refused to give her a proper diagnosis; and essentially told her the same thing your parents were told, where I would grow out of it, and it was her responsibility to make me normal.

Anna: Yeah, and that's the problem. That's the big problem on this whole scale. There is nothing normal about anything. What is normal is by the definition of a person. My dad, his mother had bipolar disorder; and she would say to my dad, who is also dyslexic and he's also autistic, "You need to be normal!" and my dad's like, "What's normal?" And to this day, if anybody says normal to me, he's like, that's just your imagination of what is supposed to be normal. But, nobody is ever normal. It's just your opinion over another person's opinion." The truth is we all are just who we are and whatever is normal is just what you want it to be. Because, being normal just means that you want us to be who you want us to be when we are ourselves. That's like one of my biggest red flags; when somebody says be normal. No.

Anna Discovers Herself through Art

Amanda Antell: Yeah. I agree with you 100%. With your story, you already talked about several questions. I'm not going to bother rehashing them. But the thing I did want to ask you was How did you find art? Art has obviously become a really big part of your life and it definitely was a healing outlet for you. So, how did you find it when you were going through such a difficult time?

Anna: Yeah, so when I was really young I actually did do art. That was my one very big passion. When I was a little kid that was really my thing. And when I got into kindergarten, they said, "you shouldn't be an artist because you're dyslexic. You're not going to get anything to your dream." And I was like, "OK, I guess I have to get into the sciences or whatever." But when I got to my 20s, it was weird. I was paled into this world like, "oh, I'm going to do some art because I like to do busy work. I'll do some coloring and whatever." But, then I've just had this feeling like I could do more. And so I started doing art again; I started painting and I started using different mediums and I started learning about how to make things. And, then it really was until my partner came around, where I started realizing my whole story and who I was supposed to be. Because, told him about vivid dreams; and I told him about this dream where this boy was crying, whatever, and he was like, "wait, that was you?". And it's really funny, because that connection was; for the longest time, we were actually having dreams and visions of each other, and we never even knew it. And he's also neurodivergent. He's autistic and has ADHD. We're both very much in the sphere of having disabilities and we, nowadays, accept it. But, it was really when I started; I understood, "oh, these dreams. Who I was. There was a purpose." There was a place. Things were happening for a reason and it's weird. I had a dream this week and I was talking to a friend of mine, who's also dyslexic, and he's like, "wait, that was how I felt." And I was like, "yeah." My dreams are always what makes art. I have a dream like a great dream and it's about something. And then somehow I find out that there's something true about it, And then it connects, and then I make this art piece about it. I love to put the story in the art. And that was really where it started blooming; when I started putting the stories that I found and the things I found into art. With my partner, I found out about his family and his background and they go all the way back to Egypt and to King Tut. And [I] found out that King Tut never was able to really speak about who he was, but he used his art to do it. That was really encapsulating to me. I was able to understand the same thing because I felt that way. And that's why I make art. Because, people, when they see my story, when I die and scientists are looking around and like, "where's the documents?" They have my art pieces. Each of my art pieces tell a part of my story. It's like that big huge art piece that I gave you. Like I ran away and then I came back; because it's a spiritual movement, but also my own story and where I came from. Because, I came from where my mother was very strict. She Was a teacher for a while. Actually, weirdly, she's also dyslexic. Both of my parents are dyslexic. She wasn't able to graduate and pass the test to be a teacher in Oregon, but she could do it in California. But, she didn't want to go to California. So she stayed in Oregon. But, she became just one of the helpers in the school districts and she got into many school districts to do that. But she knew a lot about knowledge and understanding; and she would teach me about some random stuff. And the knowledge she gave me made me run away, because I didn't understand what was happening. I didn't really understand that, maybe what my mom was telling me, was not the full picture. And, it was when I was in kindergarten, when they started saying, "hey, you can't be what you want to be.", that I really ran. I was like, "I need to find comfort in my life, but I don't know where that comfort is." And I was running away trying to find it when it was right in front of my face. And that was when I actually had to go through so much in my life and I was hurt so much and there was other people that were like, "I don't understand you.", and I was trying to grasp and find somebody that would help me. Somebody that cared about me. Somebody that was there for me; other than my parents. And, I finally found that. I came back, like literally just came back. Because, I was like, "there's nothing here." And the person ran after me. The person was always there; I just never realized there was something there. Or I didn't realize there was More to my life than I understood until later on. It was like I had to do a turning point and had to go back; and that's really when the art bloomed and that's really when my understanding of what I was supposed to say and what I was supposed to do bloomed. It also gave me a great way to start getting more spiritual; understanding things that other people might never know. Or finding things in history, where other scientists can't understand it. And I see it and I'm like, "oh, yeah, that's this!" It's always fun when they're arguing about people with disabilities and then you find out, because you're neurodivergent, you realize, "Yeah, that person has this disability actually because all these things go together and because I am neurodivergent I'm the same way." You can understand it, and you don't want to tell them. But, you have all these things you understand and you can connect with. And you're like, "well, I know it and I'm gonna say the truth because that's what I do." I've been around where I was scared to say the truth; and I was like, because my life is not good enough. I thought my life wasn't good enough. My story wasn't good enough. But, then at the end of the day, it was just me not understanding if I was. Art became what it is today, because I finally understood me. So I was making some music for my degree and I was in some classes and two of my composition classes, I made these two different music and I put them together and then I put a vocal track on top, I found out they'd gone together. Like they were supposed to be together. I just never noticed it. these puzzle pieces and everything melds together. The thing is, they're separate, but then they finally find a place to go. That's how my life is. there's this part, and this part, and this part. But, then finally I had to take them all and put them together. And art was that catalyst. I put everything together.

Amanda Antell: That's incredible. So one of the pieces that I really liked was the really big one with the religious writing where there were like multiple facets. You said that, before, it was a really deep reflection of your journey and you talked about this a little bit already. But, I was wondering if you could expand on that, with that specific piece, as well as the significance of the figures and the religious text in the painting. Basically, what made you choose the specific passages that you chose for the painting?

Anna's Magnum Opus: The Design and Process

Anna: Yeah, it's interesting. Because, that religious text was not actually originally on there. I first painted it and it was just from the dream I had when I was a kid when I was running away; me and my partner, who we are, and the other things I had in dreams. But, then somehow I found this religious text and I read it and I was like, this is my life. This is talking about running away, then coming back. So I started writing it, and I made it different fonts because it's being written on stone. The painting itself is supposed to be hieroglyphics. So, I was trying to recreate like a finger writing it and underlying the really important things. And I put it in gold because something I'm really a passionate about is King Tut and he was a goldsmith and, people really don't know this, a lot of his art pieces are actually in his tomb and those were actually his own. He created them and he did gold tinting; he also did goldsmithing, he would embellish things with gold, he also made art pieces. Like his staffs were all made by himself and he would use each staff for when he would go to court, whatever. Like, who was there that day; he would be like, "okay, I'm going to take this staff." And actually the reason why you need a staff was because he couldn't walk. He was actually a toe walker. He also made himself his own golden toes. He made himself his own little umbrella thingy. I like to symbolize it with gold everything, because of him and how he was using gold as his catalyst. And so that's what I used the gold writing. It's actually, Isaiah 30:15 through 18. And it's written on there. And, actually another thing I put on there later; after I put everything was, the "he" and "love". Because, my partner talks about this; he made some music and he was like, "yeah, this is my king piece." And I was like, "okay." Because, I talked about that and it's weird because our nicknames. My name is Anna. It means "grace". But, if we get really deep it really means "love". And his is a lot of times known as "he" or "peace". So I put that in there. So, "he" actually goes to the Egyptian God, who was supposed to be for the waves and tides at the Nile, in Egypt. So that's where that comes from. And then the hands are actually my own hands. One is him grasping. He's like, "I'm holding on to this.", and mine is touching it; making that indent into this, because I'm remembering it. So, each of these things are supposed to be dreams or who we are. When I started running away, I had this dream. It was weird. It was like I was running away from something. Because, in this dream, I was being held by a mummy and I had to get out. I got out, cause I didn't know who this was and I saw all these hieroglyphics on the wall. My mom was holding my hand and was running me away. Then she got captured, but I had to stay. And, I go into the Nile, and then there was this hippo, and there was also this crocodile, and the pointing of the Pharaoh. Me being almost prisoner into this water and me going out of the water and then coming back in and running back. But, still there was a lot of things that was gonna hurt me and try and take away my freedom and who I was. It's like reality in full; me being persecuted in real time, and also spiritually what was happening. Just sandwiched together. you see this as reminiscing and understanding where I came from, and who I was, and how I actually had to get back to where I was supposed to go, and the art I was going to make and the things I was going to create, and how I am now.

Amanda Antell: Again, very incredible. I'll be honest with you; I was one of those people, who would go to art museums and appreciate what I was looking at, in the sense, that they were beautiful paintings. But, I wouldn't think a lot about all the work and all the emotion that went into them. But, after talking with you and you explaining how you made this piece; I have a lot more respect for artists now. Obviously every artist has their own process, but I never thought about the emotional aspect artists put into their work, if that makes sense?

Anna: Yeah. I think it's really funny. Because, when I gone to these fancy art museums; cause, I gone to Europe for a singing assignment when I was in high school. And I come to France, and I got to see these art pieces. Everyone else is just going and looking at them and like, "Oh, they're so pretty!" And, I'm over here looking at it, "I see the detail here." I only have to look at it for a couple seconds and then I can walk off and see the next one. Because, for me I can get really detailed just looking at it for a couple seconds. I don't have to even be there for a long time. I think it's really funny when I'm singing or making art; everyone says, "Oh yeah, paintings take hours and days." And I'm like, "I could put two art pieces in a day, if we're talking about 24 hours. Or, I can do one a day." Like I can make art off the bat. I go back to it and put the lines in, or whatever. Because for me, I see things, I do things, and I can put the detail in with it. A lot of people have this process. You need this process to make things. But, for me, I don't use a process. I do everything in a way that makes my brain understand. The detail might be added the same time or, really, I don't finish all the detail because I'm not really happy with detail because I can't find the right tool. And then, I finally find it and then I'm like, okay, I'll go back and do really nice detail and do some more shading. But, a lot of it is done in probably 30 minutes to 4 hours, or even more than that. So, it's whatever painting I'm making and how big the thing is. But, I can do a lot of my art pieces very quickly because the emotion and the understanding I see in detail is really different than most people. I'm in this one class, it's talking about AI and arts, and we were seeing this painting that AI made, and I can tell that it was made by AI because of the texture and everything. Everyone else is looking at it like, "I don't see that. I don't understand you." I'm like, "I can see it.", And it really flusters me because, I can tell what you're making it out of; what you're doing. And then, maybe I see in the corner, there's a shadow of something else. It's weird; I see things differently. And that's also just part of myself, because all artists see things differently, and all artists have different tastes. But, I think when it comes to being who I am and being dyslexic and all that, we also see things very different than a neurotypical person in the art sphere. It's always funny when I'm the non neurotypical person in the art room and I'm looking at it and I'm like, "I don't see what you're struggling in." Somebody asked" how do you manage time and all that?" And I'm like, "I can get things out pretty fast. I'm pretty detailed and I see things. I do things maybe a little different than you, because that's who I am. And I'm not bothered by it. And when I get passionate, I do it from the heart."" so, when I look at art, I can tell was this from our heart or if it was just from them being told, "Hey, we want you to paint something like this." And then they do it. Is the heart in it or is this something they weren't really passionate about? They just painted it because somebody paid them. I can tell all the meanings and betweens. A lot of the other people like, "oh, this painting is so wonderful. "And I'm like, "It has no meaning. He did that just because. I don't see any meaning that I really would connect with." when it comes to art, I'm just a little bit different. But, at the end of the day, a lot of this stuff I was seeing was just made to be put out for money. So, I was seeing things always different. And then everyone else was looking at it like, "this is cool. It's nice.", and I'm over here like, "that's great." So when I talk about art, it's going to be totally different than the next person and everyone else is going to see it totally different. It's just who I am.

About Special Interests

Amanda Antell: I think that's actually pretty awesome, and the way you talk about art and how you can put out pieces so fast; it just reminds me of autistic people and what we call special interests. Special interests are basically what our passions are. And with autistic people and our passions, you probably already know this with your partner, but we can just go hours and maybe even days if we are really into something without stopping. For me, it's animals. If it's anything related to animals, I could put out work really fast and really high quality work. I can write a 20 page paper in three hours, easy. Maybe even less if I'm not distracted and if you don't account for sources. It's the same thing; if you're passionate about a painting or if you're just really inspired, you just have to get it out. Because, it's in your system and you can't not write about it or you can't not paint it.

Anna: I had to do like this image thing with AI for my AI class. And it was so aggravating, because the image I had in my head; I couldn't do that because the AI thing wouldn't understand it. So, then that was really a hard thing for me. Because, I have to swallow my pride. I have to swallow this understanding and who I was because that was how it was. So, yeah, I understand. It is passionate. It's like one of those things that I'm passionate about, but it's also weird. Because, for you, it's like something you really obsess over. It's like a topic or something. But for me, it's more like a broad spectrum. It's just like I have this vision; I have this dream and I'm like, "I don't want that dream to be lost." So, I have to quickly do it as I remembered it. So, that's why I do it. And they're all in different like spectrums and understanding. A lot of them are my obsession, my passion, which is about Egyptology and King Tut. But, a lot of it is just all different things that I've been dreaming or whatever. Something I've been seeing. So, that's how I make my art.

Amanda Antell: So, It definitely doesn't come to me in dreams or anything like that like with you and your art. But, what I would say, it's been with me since I was a little kid too. In fact, in kindergarten, to escape that abusive teacher; I would actually go to the elementary school library. When we had a couple of corn snakes, a hedgehog, and I want to say like a bearded dragon there. We had an iguana, but the iguana was really grumpy. Anyways, the librarians were aware of my situation and they would just let me feed the animals and hold them. When I'm with animals I can forget how anxious and how upset I am and even the other day I was really stressed out, and Corvallis was doing a sheep production lab, and I was petting this donkey that was a herd guard for the sheep for half an hour. I wanted to steal the donkey, but I didn't. Anyways, I understand your passion. I understand how you get into your art so easily. Because, I'm the same way with animals when I see one. I also wanted to ask you, would you say your process for music is pretty similar to your paintings? Does a rhythm come into your head when you dream or do you get inspired through the day?

Anna: So, I will have sometimes a dream or something with music in it, but I won't even understand. I will forget about it. Like totally forget it. I will remember pictures, but I will not remember music. Which I don't understand why. But, that's a whole different thing. But, when I make music; like you give me, "this is what we want" and a rubric. And I will be like, "okay. Yeah, totally." A lot of times for me, singing is the first thing. So, when I think of songs or music; other music inspires me, or I'm just at home and I start singing or whatever, I'll record that and then start making it off of that. Or sometimes it's weird. Like I randomly just play and I start making a harmony. Because, I just feel like, "Oh, I need to do some harmony right now." It's a really different process; which is interesting. Because, you would think they would be the same process. But, they're not. Music, on the other hand, for me, is something that is just random, sporadic. I'll start singing and then I will forget about it. Or I'll record it because I feel like I wanna record that day. I'm getting better at it. So like, when I am singing, I record it. Right now trying to make an album. I call 'em like psalms kind of thing. I write poetry and stuff, and that's how, the same way, I sing. But, then I'll start putting chords and other things that I feel like textualize. I like a little more Middle Eastern sometimes, I'm more into that. When I really started making music in college; I was really into something that was very nice and easy, but a little more Middle Eastern. I like to find a story that I was really interested in or something like that. That's really where that comes from. Paintings, on the other hand, they will come from just random things I'm thinking. The songs, a lot of times, do not go with any of my paintings. Sometimes they do. That is very rare though. A lot of times I'm not even aware what I'm doing with music. Whereas, I am very aware what I'm doing with painting. So, when I'm using my hands and not just making songs; I'm more aware and I have a bigger picture and understanding of what I want to make. Whereas, with music, it just comes to me and randomly i'll just do it, And find what sounds good and then find out there's something more to that. So, it's a total different process. It's like a different part of my brain is being used for both of them. Which is really cool. They don't overlap always, but they also do work very well. And I think that's because a lot of my life I was in choirs and things like that; and so I never really made my own music; as much as I made my own paintings and understood that I could do that.

Attitudes Toward Dyslexia: Evolution Over Anna's Life

Amanda Antell: That's super cool. I want to shift gears and talk a little bit more about the attitudes about your disabilities. How would you say the attitudes surrounding your disabilities have changed in your adulthood? Or would you say that they have stayed the same?

Anna: Yeah. The attitude of dyslexia is pretty much the same, but my attitude has changed. And because of who I am and how I express myself, that's really what it is. So when we think of the attitude of others, the attitude of others feed off of you yourself. If you're able to advocate for yourself and you understand who you are, that really helps. So when I was a kid, I didn't understand myself and I was more dependent on the other humans, because that was when I was a kid, I had to have adult supervision or whatever. And that really impacted my life. But as an adult, I'm able to see things and do things by myself. I'm able to be more independent and by doing that, the attitudes around people have shifted because now I understand who I am. I verbally say I'm dyslexic and whatever, but because of who I am and how I rate the space, then people's attitudes change around because I'm one of those people that they don't probably even know I'm dyslexic if I don't tell them because they just think you're kind of strange or whatever. And I don't try to become too scared, but I'm not too like forcefully up in front. I'm just trying to be me. And I'm trying to give that space and to give understanding, but also get that conversation moaning or whatever. So the shift is more because of the people I'm around, the things I've been through and the understanding that now I'm adult and I'm going to engage with people a little bit different than when I was a kid. So to the government standard, nothing has changed. I don't see anything has changed. Most people don't even understand what dyslexia is. But my mentality has changed to a point where the people I'm around and the things I'm with shows that I'm not getting persecuted the same way because I'm more capable to do things and I understand who I am So I branch out and I do the things I'm good at like art and music And people see that and they acknowledge that and they respect that. They don't even know that, Oh, it's a person who's dyslexic, they just see me as me. And so they're not going off in like persecuting me. A lot of times it's on the bigger picture scale where they're just like, Oh yeah. They just lump you in with everyone. They don't understand it. That's the mentality.

They just see you like. Oh, you're one of us, but then you find you're like, no, I can't do that. And then they're so surprised. And then they're just like, why? And then we get into a conversation, that's the mentality I'm seeing. The difference and shift, and the change of people's attitudes.

It's not because the disability is self, but it's the person and the freedom I have. So by having more freedom, having more time, having more understanding, the persecution I had before becomes less prevalent. I'm less in danger of being persecuted for those things and get my rights taken away because I'm able to be who I am and being free. And I'm also have the mentality of myself of freedom and understanding of expression and I know who I am so I'm not as dependent on others for that. If you're dependent on that person or dependent on others more it becomes more easy for them to hurt you and to persecute you, and That's where that becomes the problem. And that's why as an adult I see the difference there.

Amanda Antell: Totally. So for me for autism. Like I said, in the nineties and even the early two thousands it was basically thought of autism just didn't happen in girls and people raises girls. But even like in the mid two thousands to now, the diagnostic spectrum has widened certainly to where adult women and people raised as women who are now adults, they're getting latent diagnoses for their conditions and now the medical community is discovering, "hey, we really screwed up here" and we see similar trends with people of color as well where because the traditional diagnostic criteria of autism and ADHD as well was essentially young white boys. And now it's expanded to people of color and women and people raises women. And in terms of attitude towards me, I always disclose my autism very early on to professors and people I work with. And generally it's a pretty mixed response. Sometimes people don't care. One time I got in fantasized and the other time professors just have this idea in their head, like what autism looks like. It's usually like from good to Dr. Big Bang Theory and they're surprised what I have trouble with and that I need a lot of specifications with assignment structure. And I don't know if people try to discuss dyslexia or dyscalculia with you and you disclose but for me it's like even when I try to just discuss my autism and try to explain "autism is not the same between any people, anyone", and "this is my autism. You really need to listen to what I need," a lot of professors really don't understand that. They just keep making assumptions and that's just annoying even though there's like more official recognition with my disability now. I'm not sure if you've gotten that too with dyslexia and dyscalculia where people just assume what you need versus actually listening to you.

Anna: For me, it's kind of different because I'm a music major and a lot of musicians have disabilities. I will tell you, I've worked with people from the whole broad spectrum of disabilities. And I see that all the time people in the art community, almost all. Of us have a disability in some way. Or we don't know we have a disability, but we still might have one and they just don't know. And so when I speak like, "oh yeah, I'm dyslexic, that's just because I'm a dyslexic." They don't really care because we're all artistic and we all have our own special differences. We're all a little weird and funny and we're all whatever and we all have disabilities. The only time it really becomes a big thing is when another dyslexic is with me. So then when I'm like, "Oh, yeah, I'm dyslexic too." And that's really shocking There's a broad number of people that are dyslexic, but not a lot of them have been tested for it. So then they don't really know they're dyslexic. So then if I see another dyslexic person and they say, "I'm dyslexic", then that's when it's like, "Oh, that's cool." But most people, they look at me and I'm in the arts and all that, they just see me as "you might have a disability, but we just don't really think that much". For me, I've learned how to cope with other people, it's been a lot easier. And by me being in the music and the art background we don't need as much help in that way because I've been doing so much music and art in my life that actually I'm more advanced than most of the people I'm working with in some ways. And sometimes I'm like, "oh yeah, I know that already or whatever." I don't actually have to go to the teacher and say, "Hey, I have a disability." It's just known that, "yeah, she's disabled". People are afraid to say they're disabled, but I'll email you and say, "Hey, I'm dyslexic. I just want to tell you". It's so people are more open and they know that I'm gonna be different, and they accept that difference. I've only had one teacher that really doesn't grasp the idea of dyslexia or people with disabilities, but I don't talk to him because he's strange himself and there's some things with that and he knows me by now that he just reads my body language or understands that she's a little different. So most people who know me, they just get to know me cause I'm so open and welcome. They don't think about it. They don't think about my disability, but they think about me as me. So it's different. It's kind of nice. Thanks. But also my disability is one of those things that it's not totally hindering me because I've learned ways to cope and mechanisms to work with me. So then I don't have as much problems. The only time I've ever had one person that was really bad to me was a math teacher because I had a disability. And she just got really mad. It was on email that she did it. And I was like, "okay, great." luckily, I wasn't face to face with her. And I've actually known, because of the baggage I've had, I don't totally disclose that I'm dyslexic always, and then that's another thing. But, yeah, for me, it's not the same as you in the way of like, hey, they don't really understand it. They do understand about learning disabilities, but they just don't know how to help you. So they will ask "what can we do to help you?" The thing is, because dyslexia is so shush, then that's the problem. Like when dyslexia is so shush, it's where they just don't care. But when, like autism, people are fathomizing it as things they're showing it in TV and all that. That becomes the problem is when you're seeing it everywhere. And if there's great people that are actively talking about it, but there's other people that are putting it down or whatever. That's when the confusion, the commotion, that's when we need to advocate more about it. Because people just don't really know. And they just say, "Oh, it's a learning disability." And if they just look at me like, "what can we do to help you to succeed?" And because they know who I am, they're just like, "here, whatever you need, we're here for you." And they support me. So it's a little bit different. I'm actually totally in a different place than most people because I am lucky to be in a community where there is a lot of people with disabilities, so a lot of acceptance is around. But when it comes to the math and sciences, that's not always the same case. It's very different because the mentality is more about science and math and understanding of how the brain works and whatever. And because they don't see it the same way. That's when the conflict arise. So I'm lucky to be around people and be in an environment where that's not the same case. And I'm just very lucky. To not being persecuted like that.

Autism: Representation vs Reality

Amanda Antell: It's funny you say that. The reason why I laughed earlier and I did the so so thing with my hand was because autism is treated very weird in academia, to be honest with you. So basically because they're presented with ideas of what autism looks like from really bad representation, like I don't want to say Big Bang Theory, because Sheldon isn't officially stated to be diagnosed with autism, but everyone basically just treats him as that.

Good doctor, I guess I'll stick to that example, because that is explicitly stated. He is autistic, although it's a terrible representation, but because of examples like that, a lot of professors make assumptions about what I need, but it's also just that they don't know anything about autism, and they're not actually trained to deal with disabilities, especially on the four year university level, because a lot of those people who are forced to teach classes aren't actually trained teachers, so they're given this paperwork that said you have dyslexia, dyscalculia, autism, ADHD, or whatever. They're like, "okay, extra test time for you." And that's just how it's treated on a blanket level. So it's not that I disagree with you necessarily, so much as autism is just, it's like we're persecuted as well, but we're just persecuted in a different way because autistic people, at least for me specifically, I am expected to perform at a really high level because I'm so high functioning. I'm not expected to make mistakes, but because I have accommodations, if I perform too well, it's assumed I'm gaming the system. So I can't really win either way. And because we're both women, we really can't show emotions, because if we do show emotions, We're considered weak, we're considered too emotional. We're not considered rational. And I don't know, that's just the attitudes are still there with autism. It's just in academia, it just comes out very differently compared to, I guess, how dyslexia and dyscalculia are treated.

Anna: That is true. And also it's in academia, in the big huge sphere of it. It's very much looked at differently. But they'll look at me and say, "why can't you do this?" and they'll just come out at me and be like, "why can't you do this, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah." and they just don't understand I have a disability and they don't know how to accommodate for me. Whereas in the music sphere, in the art sphere in academia for colleges and that stuff. It's not looked the same way, which is very strange because you would think oh it's going to be looked the same way I have friends that are autistic, and they're very much heard and they're like, oh, yeah, you need more time to do that. I had a friend who was another dyslexic and my professor's like "if you need me to read the test out, I'll read it for you." Literally takes her into another room and reads it for her. That is totally a different sphere. It's like a total different thing. It's weird. It's like the music department and the artist department is on a different level than the rest of academia and it's really crazy. But yeah, so teachers around the music and arts, normally we're around people with disabilities. We don't listen to what those shows are, and sometimes they do have to, like, if they're really cynical about math and that stuff, yeah, but a lot of times they get heard better, and it's not a surprise. I'm like, we understand low functioning, high functioning, the whole sphere where then people in other places will go and say, "Hey, we are so surprised you are, you can't, you're supposed to not be, you can't, you need help or you should be succeeding more well or what?" I've had classes where I'm just the only girl in the class. They don't treat me any different weirdly, it's like we're all one. Nobody cares. It's just in the music and arts department, we're not looked at by our gender or by our disability. We're looked at as what does your disability give to music and art? How are you understanding the curriculum and how are you making it known? And sometimes it can be bothersome because you'll start talking about something and the teacher just doesn't understand it the same way you do, and that can be kind of confliction, but a lot of times we like people with other disabilities in the classroom because they understand things differently than us. And so we're always listening to each other. We're always feedbacking on each other. You can say you're autistic and we would be like, "okay, that's cool. Let's make music together. What are you thinking about this? Oh, I understand. You probably need a minute of break or whatever." that's how we work with it. We're totally different, where we don't see the same pictures of understanding of the rest of the academia world, where they go around and say, "You should be this way, or this show shows this," it's so weird.

Amanda Antell: No, I agree with you. I'm not saying that the way traditional academia treats disability is right by no means am I saying that. I actually wish that they were more like the arts department that you're describing. Or it's like they just embrace all the differences between the students and faculty. I feel like academia would be a much better place if that happened. I do want to get to our last question. What do you want the audience to know about dyslexia and dyscalculia? What can they do for their friends or loved ones that have these conditions?

Anna: Yeah, so I was actually talking to someone else about this one of my friends because we both have similarities and the first thing is just respect and understand we will need more time on things. People really don't get that. They're like "you need to finish up quick" and time management to us is totally different. Like we don't even have a time management idea Time is a fathom of imagination to us We need more time sometimes for things than others. And we need shorter time for things than others. That's the one big thing. People are always like, how can you have so good time management? And we're like, we don't have time management. We just are good at certain things, so it takes us less time. And we're not as good at certain things so then it takes us more time. Secondly, with that, We need supportive people around us that are understanding that we're not going to be totally perfect and they're not going to go around us and hound us that is the worst thing. We want you to be like," okay, you're having a problem with that. What can I do to help? Where are we in the understanding?" You go to the person say, "Hey, I need you to help me spell this word." Don't be annoyed. Do not be angry that we ask you. Be the person which we can ask when we acknowledge we can't spell this word or we're having a problem with the left or right. Don't be like," Hey, yeah, I just feel this and then you put it in." Don't be like that. I've had a teacher like that. Be more like, "okay, yeah, you do it differently. All right. Yeah, I see you're getting a little here. There's a problem here." And so respect that we're different. Respect we're going to be a little wonky. Do understand we're going to need more time. That's pretty much it.

Amanda Antell: Thank you so much, Anna, for talking with me today. Your story is incredible. Your art is incredible. I really hope that you had a great time talking to me today. Thank you for joining us today. I hope everyone enjoyed today's episode.

Episode Outro and Disclaimers

Amanda Antell: Thank you for listening to today's Let's Talk Autism episode. It was truly an honor for Anna to share her story with me. Anna's explanation of her artistic process in both her paintings and music were very interesting to me because they come very differently to her in the way that my passion for animals comes to me. My special interest allows me to write a good paper fairly quickly because I already have the narrative and flow established before I start writing. However, Anna sees the whole picture from her dreams or other experiences and is able to capture the very essence of it. I hope the audience has gained a greater appreciation and respect for dyslexia like I have, and will give the space these individuals need to succeed. Thank you for listening, and be sure to tune in for the next episode.

Asher: Thank you for listening to Let's Talk, Portland Community College's broadcast about disability culture. Find more information and resources concerning this episode and others at pcc.edu/DCA. This episode was produced by the Let's Talk Podcast Collective as a collaborative effort between students, the Accessible Education and Disability Resource Department, and the PCC Multimedia Department. We air new episodes biweekly on our home website, our Spotify channel, and monthly on KBOO Community Radio 90.7 FM

- KBOO